Brussels’ new Balkan strategy: Tough love

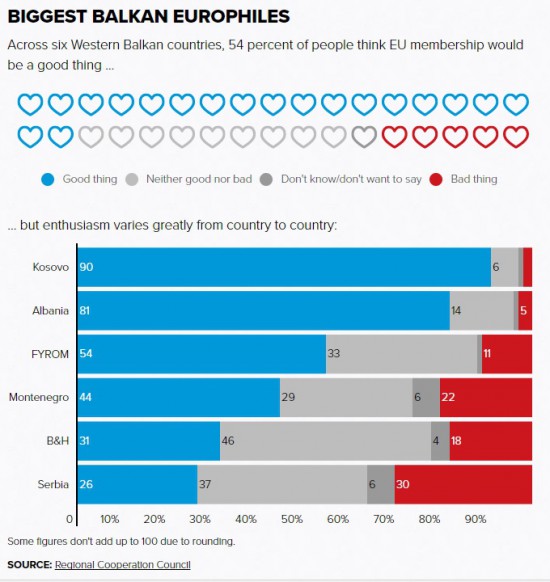

The European Commission’s new strategy for the Western Balkans holds out the prospect that two countries from the region, Serbia and Montenegro, could “potentially” be ready to join the EU by 2025. It also offers increased support for the four other would-be members from the region that was engulfed by war and civil strife in the 1990s.

But it makes clear to politicians in all six countries — Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia — that they will have to get much more serious about establishing the rule of law, cutting out corruption, cracking down on organized crime, settling bilateral disputes and undertaking a range of other democratic changes.

“Joining the EU is far more than a technical process. It is a generational choice, based on fundamental values, which each country must embrace more actively, from their foreign and regional policies right down to what children are taught at school,” says the new strategy, obtained by POLITICO ahead of its approval by the Commission on Tuesday.

The strategy aims to lay down a roadmap after Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker last September signaled a renewed openness toward EU enlargement in his State of the Union speech. The EU had previously cooled on taking in new members after a backlash in older member countries over increased immigration from poorer nations that had recently joined the bloc.

Juncker and other EU leaders have taken a fresh interest in the Western Balkans partly because of concern about increased Russian, Chinese and Turkish influence there. The 2015 refugee crisis, in which hundreds of thousands of migrants made their way to Western Europe via the Western Balkan route, also highlighted the region’s importance to EU stability.

“The Western Balkan countries now have a historic window of opportunity to firmly and unequivocally bind their future to the European Union. They will have to act with determination,” says the strategy, to be unveiled by EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini and Johannes Hahn, the commissioner for enlargement.

As part of the new push, Juncker is set to visit the Western Balkans for a week at the end of this month, starting in Skopje on February 25, an EU diplomat familiar with the plan said.

As well as the renewed drive by the Commission to deepen ties with the region, Bulgaria has made the Western Balkans a priority as the current holder of the EU’s rotating presidency. Sofia will host a summit of EU and Western Balkan leaders in May.

In a recent interview with POLITICO, Bulgarian Foreign Minister Ekaterina Zaharieva said such gatherings should become much more frequent — noting that the last EU-Western Balkans summit, in Thessaloniki, Greece, took place back in 2003.

“Fifteen years is too long,” said Zaharieva, suggesting an interval of two years between summits in future.

Zaharieva acknowledged that putting the Western Balkans so high on the EU agenda carries the risk that the bloc’s standing in the region could suffer if citizens’ hopes of EU membership were not realized.

At the 2003 summit, the EU offered“unequivocal support” to would-be members from the Western Balkans and told them their future was within the European Union. But 15 years later, only one of them — Croatia — has joined the bloc and it seems at least another seven years will pass before perhaps two more become members.

“Of course there is such a kind of danger,” Zaharieva said. “That’s why we should not create expectations that we can’t fulfil.”

Zaharieva said more Western Balkan nations had not joined the EU because the bloc became embroiled in various emergencies — such as the eurozone and migration crises — and regional governments failed to undertake the necessary reforms.

The new Commission strategy offers greater EU support to the region across a range of domains — from sending Europol advisers to boost security to making new investment commitments in areas from startups to transport infrastructure. In 2018, total EU investment in the region is foreseen at €1.07 billion — slightly more than what was spent on average in the past 10 years.

But the strategy, titled “A credible enlargement perspective for and enhanced EU engagement with the Western Balkans,” does not hold back in describing the current state of the EU’s future would-be members, declaring that the levers of power in all six countries are often in the hands of criminal networks and political clans.

“Today, the countries show clear elements of state capture, including links with organised crime and corruption at all levels of government and administration, as well as a strong entanglement of public and private interests,” the document reads.

“None of the Western Balkans can currently be considered a functioning market economy,” it also flatly declares.

Bitter pills

Although Serbia and Montenegro have been identified as front-runners for membership by the Commission, the document says having them join by 2025 is “extremely ambitious.” It makes clear that leaders in Belgrade in particular will have to swallow some bitter pills on the road to Brussels. Serbia, it specifies, will have to conclude and implement a legally binding agreement on normalizing relations with Kosovo, the mainly ethnic Albanian territory that declared independence from Serbia 10 years ago, before it can join the EU.

It also says would-be members must demonstrate “full alignment” with EU foreign policy — a none-too-coded signal that Belgrade could not continue to pursue such close relations with traditional ally Russia as it does at the moment.

But the strategy also contains disappointment for Kosovo, which is not recognized by five EU members and is not specifically mentioned as a possible candidate for EU membership in the document.

Serbia and Montenegro, on the other hand, have already begun membership negotiations and the Commission says it is ready to recommend accession talks for Albania and Macedonia too, if they meet certain conditions. Bosnia and Herzegovina “could” become a candidate for membership, the document says.

Rattled by a long-running border dispute between EU members Slovenia and Croatia, the strategy says all such disagreements must now be resolved before countries can join the bloc.

“The EU will not accept to import these disputes and instability they could entail,” the document says. “Definitive and binding solutions must be found and implemented before a country accedes.”

The Commission also hopes the prospect of new arrivals will push current member countries to reform how they operate. “The EU itself needs to ensure that it will be ready institutionally to welcome new Member States once they have met the conditions set,” the text says, lobbying for an increased use of qualified majority voting in the Council — instead of making unanimous decisions, which give individual governments a veto.

Liberal democracy activists in the Balkans have accused the EU of being too soft on regional leaders, whom they brand authoritarians with a questionable commitment to EU values. The new document does not engage in such mollycoddling and could be read as laying down the law to political leaders while encouraging activists and citizens to put pressure on them.

“Governments must ensure more inclusive reform processes that bring all stakeholders and society at large on board. Most fundamentally, leaders in the region must leave no doubt as to their strategic orientation and commitment. It is they that ultimately must assume responsibility for making this historical opportunity a reality,” it says.

6 February 2018

Disclaimer: All views, opinions and accounts included in the RAI News Section are those of the authors; their inclusion does not imply official endorsement or acceptance by RAI. The News Section reflects the selection of topics of informative value to the organization and its stakeholders. Its content is taken from press/media sources and does not in any way reflect official RAI Secretariat policy. RAI Secretariat is not responsible for possible inaccuracies in media reports.